Alexander Melnikov: The Reluctant Virtuoso

04 June, 2024

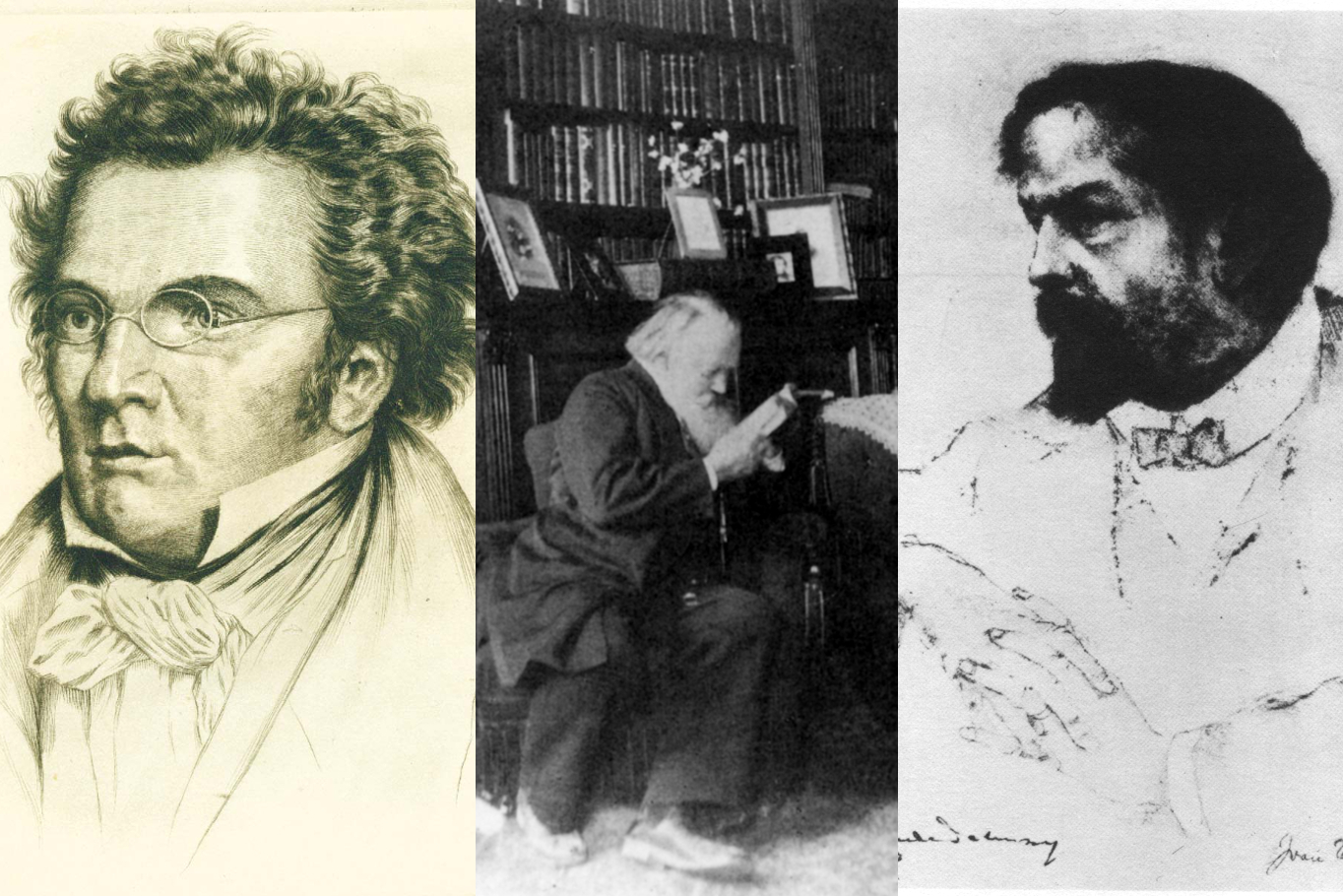

He is one of the world’s most celebrated pianists, but ahead of his Sydney Symphony debut Alexander Melnikov explains that it is the music that keeps him motivated – composers like Shostakovich, Schubert, Debussy and Brahms – not any sense of his own importance.

Written by Hugh Robertson

If you were to compile a list of the greatest living pianists, Alexander Melnikov would be right near the top of it.

With a stellar career spanning five decades, there are few superlatives left or awards to bestow on this superb musician. He is in high demand around the world as recitalist, chamber collaborator and featured soloist with orchestra, his recordings are celebrated, his recitals are praised for their inventive and unusual programming. In all things his musicianship and musicality is singled out as peerless, described by The Guardian as ‘…a steely player with plenty of ideas and charisma…’, and by Gramophone as ‘…a quicksilver artist whose uncanny sense of phrasing responds to the moment-to-moment swerves of the music.’

Sydney is in for a treat in June, with two opportunities to experience this extraordinary musician: first, performing Shostakovich’s First Piano Concerto with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra conducted by Giordano Bellincampi – incredibly Melnikov’s Sydney Symphony debut – and then a solo piano recital of works by Schubert, Brahms and Debussy.

You could reasonably expect an artist of his calibre to have an ego the size of a small planet, yet in conversation Melnikov is deeply self-deprecating and self-critical, thoughtful and philosophical about his profession, the world and his place in it. Over the course of an hour-long conversation Melnikov touches on his life and career, the futility of historical performance, the etymology of the word ‘concert’, the meaning of life (and Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life), the joy of abstraction in music and so much more, interrogating each topic with a curiosity and introspection that immediately explains the variety and restlessness of his recital programming.

In an indication of the way this conversation will unfold, we are barely five minutes in before Melnikov reveals that in fact he still hasn’t decided if he actually wants to be a performer at all.

‘This profession is very strange,’ he says. ‘I don't want to sound pretentious by any means, or nerdy or anything, but if you look at it objectively – although I can't of course look at it objectively – but if you try to look at it, this is strange contraption from 19th century. People at some point decided to play the music of the past – music written by somebody else – as if that is a normal thing. And compared to a composer, I don't think we should take ourselves too seriously – not at all.

‘I have respect and love for a lot of people that are alive who are performing musicians, but I don't necessarily have a lot of respect for the profession itself because it's a strange thing.

‘All that becomes very quickly very complex, and the opposite of exciting to discuss in an interview. But I'm always thinking that I could be doing something else, and often I actually am doing something else and trying to do something else. But I ended up being a concert pianist, which is absolutely nothing I could possibly complain about. It's a privilege.

‘But I don't take myself too seriously, let me put it that way. And I mean it. It's not some kind of coquetry. I just actually don't.’

While Melnikov doesn’t take himself too seriously, what becomes clear over the course of our conversation is that he takes the music very seriously. And for all his sardonic quips about his own work, there is no doubt his love for and veneration of the source material.

‘We have this incredible luck of this life,’ says Melnikov. ‘The chances of you or me being alive are minuscule. And then of course, it's dangerous to spend this life doing something without actually trying to think what you are doing and why.

‘There are a lot of things in this music we are playing which are actually extremely valuable, and they are impossible to perceive in any other arts form. Music deals with very important things very often. Historically, it not only deals with love and death, but fear and the meaning of life and all those little things. And very often it deals with them in a way that no other art form can because it is the most abstract art form.’

Despite this air of cynicism and fatalism, there are moments when genuine enthusiasm and excitement slips through, particularly when he talks about what it is that inspires him.

We are dealing with those exceptional things, those pieces which withstood the test of history. Some of this music people have been playing for 300, 200, 100 years. And there is really something so exceptional in those pieces.

‘And in our professional life we constantly deal with these kinds of things. It's your everyday life to deal with something which is actually a phenomenal thing a human has created. That is a driving force, of course.’

The two concerts Melnikov will be performing in Sydney encapsulate so much of what he has been celebrated for over his career. Shostakovich has been central to Melnikov’s career: his recording of the 24 Preludes and Fugues was named by BBC Music Magazine as one of the 50 Greatest Recordings of All Time, while Gramophone described his recording of Shostakovich’s piano concertos as ‘Shostakovich-playing on a level of inspiration I have only heard in my dreams.’

Of course Melnikov bristles slightly at having been ‘shoved into a certain drawer’ – ‘people perceive me as somebody who plays on a fortepiano or people perceive me as somebody who plays Shostakovich,’ he says wryly, but he readily acknowledges that Shostakovich has played a big role in his life.

The story of Shostakovich’s life is well-known, but worth repeating: a brilliant young composer and pianist with a long career ahead of him, Shostakovich’s life changed forever when, aged just 30, his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District was denounced in the pages of Pravda, the official newspaper of the ruling Communist Party. For the next 40 years Shostakovich lived at the mercy of the censors, going through periods of acceptance and denunciation, his music vacillating between inspired, original work and formulaic, ‘acceptable’ music approved by the Party. For years, convinced he would be taken away and imprisoned at a moment’s notice, he kept a packed suitcase by the door, awaiting the purge.

His First Piano Concerto, though, was before all of this, and shows the young man revelling in his extraordinary talent, as Melnikov explains.

‘This is a young composer on the St. Petersburg musical scene saying very loudly, “I have arrived and I can do this”,’ he says. ‘This is a very happy and sunny, yet deep and lyrical, kaleidoscopic work – a kaleidoscopic series of allusions to Bach, Haydn, Beethoven obviously, Rachmaninov, Prokofiev. There are a lot of allusions to other things, but it's not making fun of those things. It's just humorously and even lovingly smiling about it.

‘That’s what it seems to me. And that's how I try to play it – enjoying the compositional virtuosity. He was young and happy and extremely gifted.’

The second of Melnikov’s concerts in his Sydney sojourn is a solo performance at City Recital Hall. Melnikov is noted for experimentation in his recital programs: a famous recent project saw him perform Schubert, Chopin, Liszt and Stravinsky on four historic pianos, matching the instrument to the composer’s era; he also enjoys dedicating entire performances to a single composer, exploring all the aspects of an individual’s compositional personality.

This concert, though, is a bit more traditional, with three masterpieces by three of the great composers: Schubert’s ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy, Brahms’ seven Fantasies and the second book of Debussy’s Preludes.

‘I rarely really do this kind of “normal” classical piano recital,’ acknowledges Melnikov. ‘But these are three masterpieces, and it’s also music I profoundly love.

In the case of Debussy, I strongly believe that actually piano music does not really get better than that.

‘And in the case of Brahms, it's very touching. I don't know. Brahms is a very interesting phenomenon in the history of music as somebody who was so aware of his own deficiencies at a very young age…[but] with all this baggage he arrived at the end of his life to being able to compose something as distilled, as perfect and yet as touching as these late piano pieces. That just always makes me gasp in awe – like how is that possible? So it's very special music.

‘And the ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy is a phenomenal work, with incredibly large landscapes of unpredictable changes. It's very impressive. So it's a nice program, I hope.’