Two Cultures, One World: Deborah Cheetham Fraillon on Eumeralla

04 July, 2024

Deborah Cheetham Fraillon AO is many things: Yorta Yorta/Yuin woman, trained soprano and award-winning composer. As she explains, she had to call on all those parts of her identity when writing Eumeralla, a War Requiem for Peace – an ambitious, large-scale choral work that receives its Sydney premiere in September.

By Hugh Robertson

‘The past is never dead. It's not even past.’

That line from William Faulkner’s Requiem for a Nun might have moved into the realm of aphorism, but it is a beautifully succinct explanation of the importance of history, and its continued effect on the present day.

That line kept playing in the back of my head while speaking with soprano and composer Deborah Cheetham Fraillon about her staggering work Eumeralla, a War Requiem for Peace, ahead of its Sydney Opera House premiere in September.

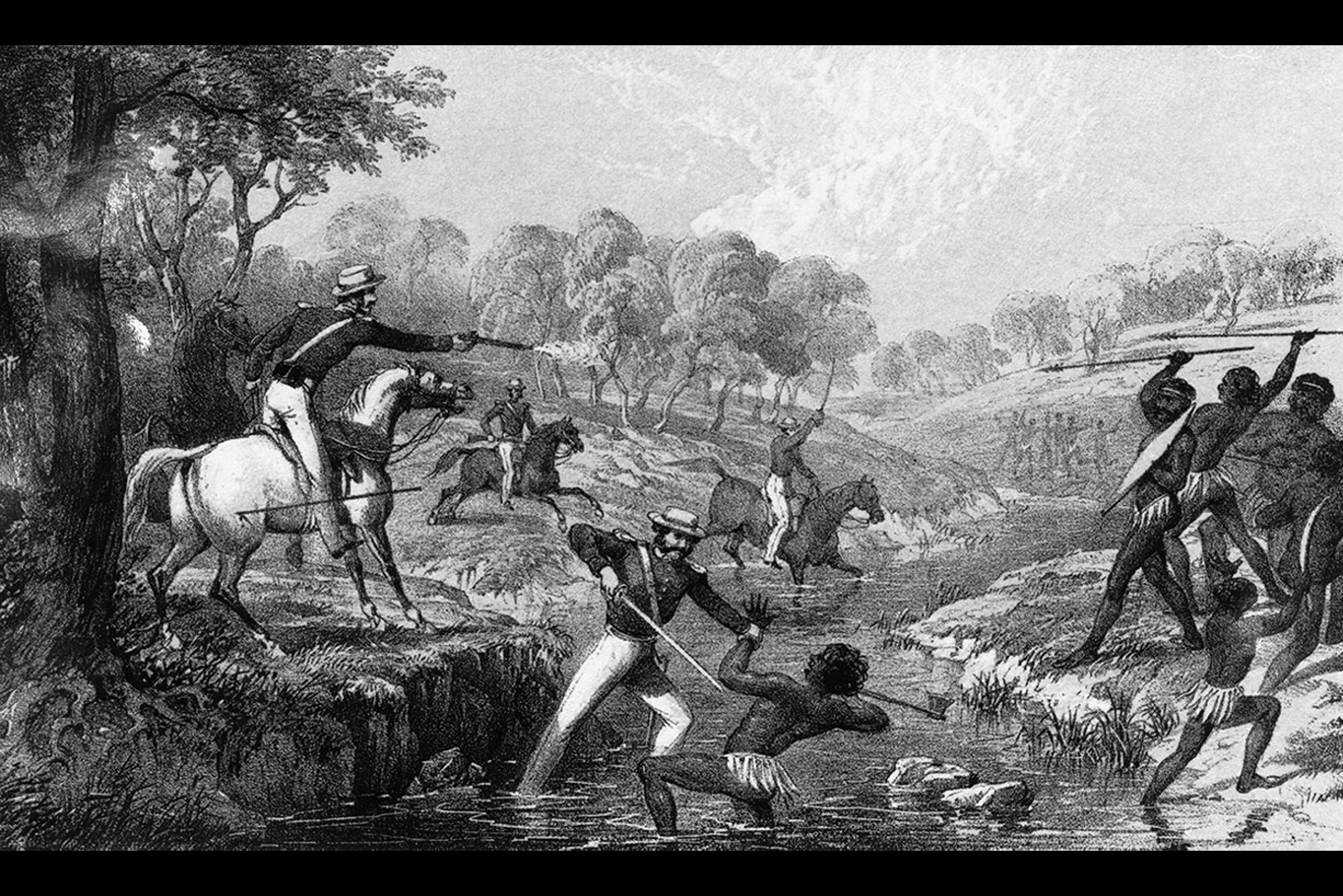

Eumeralla is an extraordinary piece of music that uses a well-known classical musical form – specifically a symphony orchestra performing the Requiem Mass – to tell the little-known history of the Eumeralla wars; a conflict in with the Gunditjmara people of southwestern Victoria were almost entirely wiped out by white colonisers in the mid-19th century.

It is a towering achievement: an 85-minute piece featuring three soloists, 150 singers across three choirs, and 70-odd musicians from the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. And it is sung in Gunditjmara language – a language that almost died out due to colonisation and government laws forbidding the speaking of Indigenous languages.

Eumeralla speaks directly to the tension at the heart of Faulkner’s quote: if we are unable to acknowledge and reckon with the ways in which our history continues to shape our present, how can we ever move past it?

That question has motivated Cheetham Fraillon throughout the multi-year gestation of Eumeralla, which all started with a visit to Lake Condah Mission, some 300 kilometres west of Melbourne, close to the South Australian border. It was there in 2013, Cheetham Fraillon says, even before she knew the history of the region, that she felt a visceral response from the land around her.

‘I was visiting Gunditjmara country for the first time, and I was standing on a veranda looking out at a beautiful sunset, and a dense scrub land that was just 100 metres away from where I was standing,’ recalls Cheetham Fraillon. ‘The beauty of that sunset was eclipsed by a feeling, a growing sort of anger that seemed to rush towards me from this dense bushland. And that anger turned into something that was truly disturbing.

It was like the feeling you have when a freight train rushes through a station and you're standing too close on the platform. It was physical. There was a sound. There was a vibration.

‘[Senior Gunditjmara elder Uncle Ken Saunders]…saw the reaction on my face. And he explained that this was one of the sites where the Eumeralla war had unfolded and that many Gunditjmara lives had been lost in this space.

‘The Eumeralla wars of resistance, and I call them that as a First Nations woman – they weren't frontier wars to us, this wasn't a frontier, this is our land – these wars of resistance took a brutal toll on the population of the Gunditjmara people,’ continues Cheetham Fraillon. ‘In 1840, the population of Gunditjmara people on their lands was estimated at 9000. At the end of the Eumeralla Wars of resistance, there were just 77 survivors.

‘It's not only a story of loss, though. It is a story of resilience. They were known as the ‘fighting Gunditjmara’ actually, and they went on to fight in all of the world wars for Australia. But the Gunditjmara were not only fighting for Australia in those wars, they were fighting for their own existence. And just recently, they not only received native title – a long-fought war that they won, but also, World Heritage listing for the lands known as Budj Bim, where some of the conflicts of the Eumeralla Wars took place. So the Gunditjmara story is one of resilience as much as anything else.

‘But before we can celebrate that, we need to understand what happened. And when we do understand, we not only know about it, but actually understand it. We can then enter into that celebration in a whole other way.’

Her profound experience at Lake Condar Mission has driven Cheetham Fraillon ever since, and compelled her to bring this story to as wide an audience as possible, realising that if she didn’t know this story of the Eumeralla wars, it was likely that most Australians wouldn’t know the story either.

‘I’m ashamed to say, really, that at that time I knew very little of the Eumeralla conflict,’ she says. And so I started a journey of learning for myself as a Yorta Yorta woman. [And] as a member of the Stolen Generations, as someone who has acquired their knowledge and their identity and their sense of belonging over a great stretch of time, I realised this was just another journey I needed to go on. That this was a kind of a hidden story that I needed to uncover for myself.’

Cheetham Fraillon understands better than most the power of storytelling. She has experienced it first-hand in her professional career as an operatic soprano, bringing the heightened drama of Verdi, Puccini and Mozart to life every night. She also has first-hand experience creating those stories: she began composing her own works in the early 2000s, and has since received major commissions for many of Australia’s leading performing arts companies. Perhaps most significantly, she is the composer of Pecan Summer (2010), the first opera written by an Indigenous composer.

But when it came to writing the story of the Eumeralla wars, she quickly realised that opera wasn’t the right vehicle.

‘I wanted to reach as many people in terms of those performing the work as I possibly could. And so instantly, I saw large scale choir, soloists, orchestra. It was then that I realised that for me, it made sense to go with a known genre within choral work – and that is the requiem.’

In the Catholic faith, the Requiem Mass has a set number and order of sections. But over the years various composers have chosen to omit, reorder or truncate these sections, depending on their aesthetic choices: the most famous part of Verdi’s Requiem is the Dies irae (‘the Day of Wrath’), all hellfire and brimstone; Fauré and Duruflé, by contrast, focus on peace and salvation, their requiems more about consolation than damnation.

While she was composing her requiem, Cheetham Fraillon realised that some parts of the content and structure of the mass was grossly inadequate and inappropriate.

‘I had been working through the movements of the Requiem and I came to the fifth movement, the Agnus dei – ‘Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi’, ‘the Lamb of God that takes away the sins of the world’. Such important symbolism for Christians all around the world. And yet for the Gunditjmara people it only represented horror. The Gunditjmara people were massacred, murdered, and lost their lives in the Eumeralla wars because of the disposition of their land. And what was that land used for? The grazing of sheep.

‘I couldn't use this symbolism in Eumeralla, a War Requiem for Peace. I realised at that moment there would be many points in the Latin Mass that just would be in conflict with the experience of the Gunditjmara people from that time. So I began to develop, lyrics and a libretto, if you will, that would allow those singing the work to understand what happened, to place themselves in the position of the Gunditjmara people.’

Cheetham Fraillon also had to reorder the movements in order to make the story not only logically, but dramatically coherent.

‘I was looking at the Kyrie – Kyrie eléison, Christe eléison, Kyrie eléison. And this is essentially an ask for forgiveness or mercy. ‘Lord have mercy. Christ have mercy. Lord have mercy,’ she explains.

‘Quite often, the Kyrie eleison would take place early on in the mass. But I have placed it second to last. Because there is absolutely no point asking for forgiveness if you actually don't know what happened.

‘I felt that the audience, the choirs, the soloists, the orchestra – we really need to go through what happened together, to at the very least know about the horrors of this war. But more importantly, take that journey from knowing to understanding. And when that's…when that journey is experiential, it can lead to a real wisdom and enlightenment, if you will. By the time we get to the 18th movement of Eumeralla, a War Requiem for Peace, we are ready to ask for that mercy, that forgiveness. Forgiveness that we didn't know, forgiveness, that perhaps we didn't bother to find out or we were resisting knowing.’

Cheetham Fraillon takes great pains to stress that Eumeralla is – as the full title suggest – a work for peace. A work to foster understanding. A work to help all Australians understand the past, acknowledge the pain, but ultimately to move past it into a future together.

‘It was important from the outset that this should work towards reconciliation, and bringing peace to the souls of those who lost their lives in this conflict, and those who've suffered other atrocities ever since,’ she says. ‘But also to help non-Indigenous Australians find a way into this story. And music can do that. It can transmit a truth more accurately than just about any other means I know.

Eumeralla aims to transmit truth not just to those listening, but also those performing.

‘This work, like so much other music, has the potential to create a space for us to learn and to grow through the process of performing, through the process of listening,’ says Cheetham Fraillon. It's part of the reason why I wrote this work – never that it would just simply be included in a program, that it would be performed.

‘I wrote it at a time that I really felt Australia needed this knowledge and needed this journey. And so far, each and every time I've approached this with a new ensemble, a new orchestra, a new choir, there have been journeys of great importance that have been shared with me. It's an uplifting and also an empowering sensation as a composer to know that your work has touched someone in such an important way.

‘Language is so closely associated with identity,’ she continues. It informs our identity in such a powerful way. And for that reason, indigenous languages was suppressed: take away someone's language, and then you take away a huge part of their identity.

‘And so I wanted to flip things around, and help those in the choir and the soloists involved to enter into this experience via the identity of the people, via their language. And once you do that, you take people through a process that they're familiar with.

‘Most choristers I know are not fluent in Latin. They have to learn it to sing most requiems, or German or French. Most of the choirs that have sung Eumeralla, are quite familiar with taking on a language that's not their first language. But in this instance, it has that additional meaning of taking singers into the identity and the head space of Gunditjmara people in a really practical way.’

That coming together of classical traditions with First Nations history and culture is one of the most fascinating aspects of Eumeralla. That in and of itself is not unique – First Nations composers have been incorporating traditional stories and music-making into ‘Western’ classical music for decades – and indeed that synthesis is the story of Cheetham Fraillon’s life. But she is very clear that this is not some coming together of two polar opposites, that the Indigenous part of her lives alongside the classically-trained opera singer and composer – not as distinct entities that occasionally bump up against each other.

‘We live in one world,’ she explains. ‘I’m not walking in two worlds. I just have perhaps a broader knowledge of the world that we all walk in than someone who has not encountered this part of our history. Certainly there are many, many histories and people’s realities that that I don't know about. And hopefully I'll live long enough to continue to grow and develop my own understanding of what it is to stand in someone else's shoes.

‘That's what develops us as human beings, yes? To develop that empathy for one another so that we might understand what it is to walk through this world together. But it is most definitely just the one world.

‘Music began here on this continent, the oldest music practice in the world,’ she continues. ‘And everything that everything that has come since is a continuation of that. Everything that we celebrate as classical musicians is simply a continuation of the need to express what mere words alone cannot tell. To elevate thought through music belongs to every creature on the planet, not just humans. And so the fact that I've studied the Western canon of music and performed music from the early 1700s up to the middle of the 20th century…I don't see that as, somehow diminishing my indigenous identity.

‘I think that any knowledge that has come to this country is ours to treasure and to embrace as Indigenous Australians, alongside all other Australians. I don't think it diminishes this work at all. In fact, I know that the marriage of Gunditjmara language and dialects with a Western tonal world, if you like, that is a really special union.

And when that comes together, through the orchestra, the choirs, the soloists – that is what is the great and lasting impact of the work. Music is a space where cultures can come together and do frequently.’