Olivier Latry: The King of the King of Instruments

21 June, 2024

A teacher at the Paris Conservatoire and one of the titled organists at Notre Dame cathedral in Paris, Olivier Latry is one of the world’s most celebrated organists. Ahead of his return to Sydney, we discuss his place in the rich tradition of French organ music and the unique instrument at the Sydney Opera House.

By Hugh Robertson

The organ is a remarkable instrument. Or, rather, organs are remarkable instruments; unlike most instruments which are fundamentally the same around the world, each individual organ is its own beast, shaped by a whole host of variables from its size, shape, action, mechanics, materials – and, especially in the case of the Sydney Opera House organ, by the very building in which it is housed.

Organs are also wildly different from country to country, even when those countries are neighbours: France and Germany each has a rich organ tradition, but those instruments can be a world apart even when only a few miles from each other.

Perhaps nobody embodies the French tradition like Olivier Latry. One of the titled organists at Notre Dame cathedral since 1985, teacher at the Paris Conservatoire, in both roles Latry is part of a long line that reads like a Who’s Who of French music: Gounod, Massenet, Messiaen, Fauré, Farrenc and Franck, to name but a few.

In July, Latry returns to Sydney for a concert steeped in that French tradition. Together with conductor Stéphane Denève (another graduate of the Paris Conservatoire), they will present music by Guillaume Connesson, Francis Poulenc and Camille Saint-Saëns, showcasing not only the rich history of French music but also, in Connesson, its exciting future.

‘That's true that we have this relationship with the organ, especially because the organ had always a very important part in liturgy [religious service] in the 17th and 18th century,’ says Latry from his home in Brittany, the region of northwest France that juts out into the Atlantic.

‘Then in the 19th century when the organ became more a secular instrument, not an instrument for the church anymore…many of the composers of that time started to compose pieces which were just made for the concert and not for the church anymore. So we had both directions, which helped to enlarge the repertoire of the organ – and made it very famous of course.’

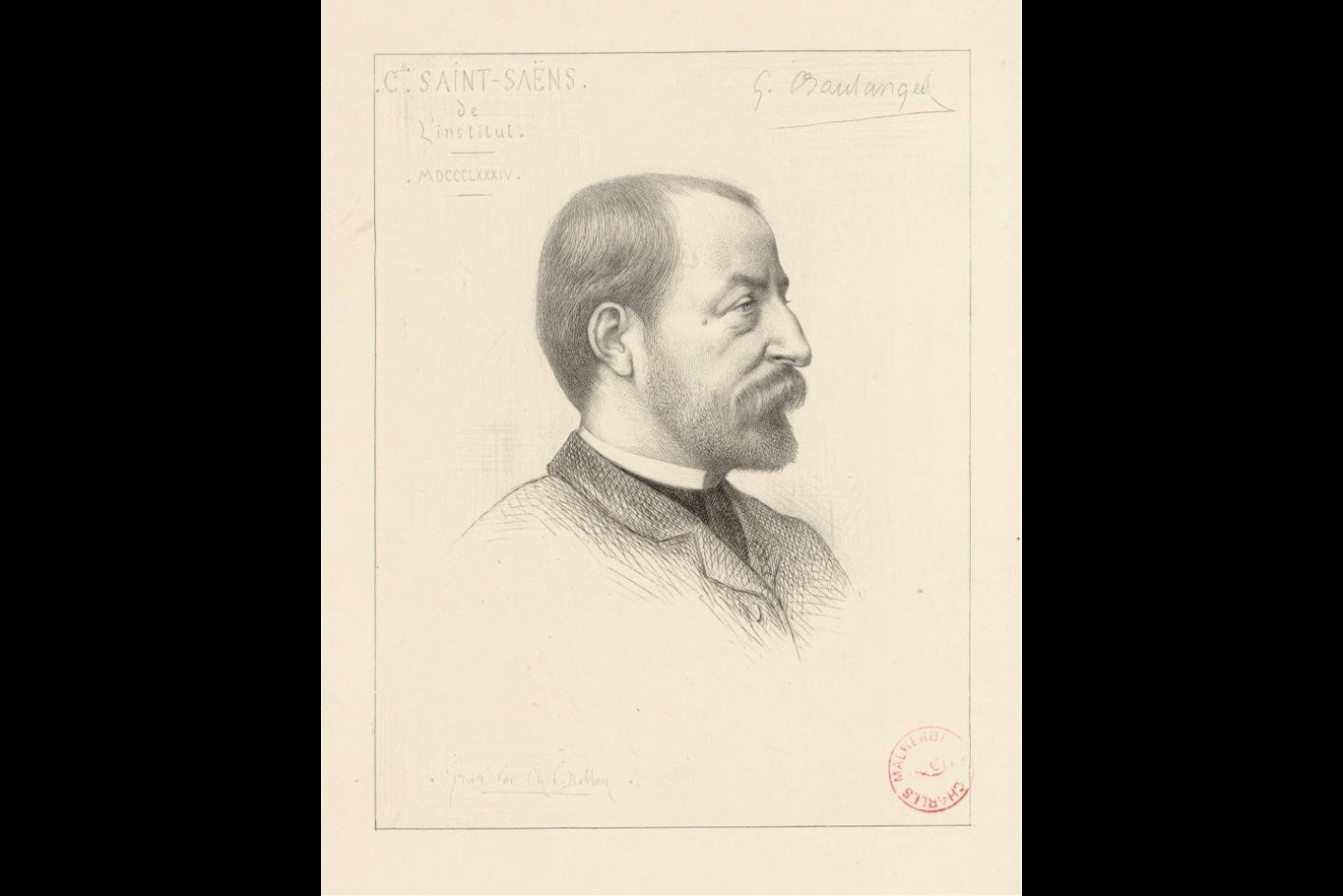

One of the most famous French composers, and one synonymous with organ music, is Camille Saint-Saëns. A musical prodigy, he gave his first public performance at ten, then after studying at the Paris Conservatoire became a church organist, rising rapidly to the post of organist at La Madeleine in Paris, the official church of the French Empire – it was there that Franz Liszt heard him play and declared him the greatest organist in the world.

Saint-Saëns wrote his Third Symphony – ‘with organ’ many years later, in the 1880s, by which point he was famous all over Europe and generally regarded as France’s greatest-living composer. It was the last symphony he wrote, and some see it as an autobiographical work looking back over his own life. He himself said, shortly after its premiere, ‘I gave everything to it I was able to give. What I have here accomplished, I will never achieve again.’

It is a stunning piece of music, full of beautiful passages that allow the (unusually large) orchestra its chance to shine without the organ. Then when the organ comes in for the finale, it crashes in with enormous chords that can shake the very foundations of the concert hall.

Saint-Saëns also knew what to do, because he was an organist himself,’ says Latry with a smile. ‘And he really knew what to do to make the organ sound good with the orchestra.

‘At first the organ is just the accompaniment of the strings – just to support the orchestra…Then in the last movement, this is all about the power of the organ.’

‘Saint-Saëns understood that perfectly, because the organ has this power, and each time he needs to have the organ join, for example, with the brass or something like this, it is always on a special way. Each time it reinforces the effect of the organ in different ways. It’s very, very smart, I would say, to think of something like this.’

(Funnily enough, despite the enormous sound of this symphony, it is best-known in Australia thanks to a very small pig. When writing the score for the film Babe, Australian composer Nigel Westlake used the theme from the finale of Saint-Saëns’ symphony for the song Farmer Hoggett sings to his porcine companion, resulting in the cherished scene in which he leaps about the farmhouse singing ‘If I Had Words.’)

Latry feels very keenly his connection to Saint-Saëns, and indeed to the whole French tradition. Among his many other roles – international soloist, recording artist, published author – he has been, since 1985, one of the titled organists at Notre Dame in Paris, perhaps the most famous church in the world and a bastion of French organ music.

‘I remember the first mass that I played there as an organist,’ recalls Latry. ‘I still remember putting my hands on the first chord, and thinking “so many people played that organ before me in that space.” You have this weight which is just horrible on your shoulders.’

‘And speaking about Saint-Saëns and the French tradition…all the French organists went to the Paris Conservatoire. And I remember when I was 18, my teacher Gaston Litaize was speaking about Louis Vierne as his father, because [Litaize] was a student of Vierne. And then going further, he said “César Franck was my grandfather.” And then I was 18 and I was thinking to myself, “well, Louis Vierne was my grandfather and I am the great-grandson to César Franck.”’

‘And that's true that being a teacher at the Conservatoire for 30 years, we have this link. And we have to give to the people this tradition which goes in several ways. It's not only playing in the way they played 30, 50 or 100 years ago – it’s also speaking about all the stories that you will never find in any book. And those stories are very important to understand the French spirit.’

‘I remember many organists that I met when I met when I was 20 who were 80,’ continues Latry, ‘which means that they were 20 during the 1930s – so they have met Ravel, they have met Florent Schmitt, Widor, Vierne, Honegger. It was quite something for me to speak with those people and having the link like this. This is something I remember: this link can exist in many ways, but having this first testimony of music history is very, very important.’

This inheritance is especially front of mind for Latry at the moment: as we speak, he is in his final days of teaching at the Paris Conservatoire – he says he is looking forward to being able to play more concerts.

‘This last year I really organised my teaching to not only to teach people how to play the organ, but also to speak about the stories. I was very close to Olivier Messiaen, and speaking with the students about Messiaen, I was exactly in the same situation that I was when Gaston Litaize spoke about Vierne to me. And I hope that in 40 years they will speak to their students about this relation that I had with Messiaen – I think it's very important to have this consideration.’

For now, though, Latry’s focus is on Sydney, and his first performances with the Orchestra since 2015. He has very fond memories of the Orchestra, the Sydney Opera House and of the organ, and is looking forward to experiencing the new sound of the revitalised Concert Hall. But, as always, a big part of his rehearsal will simply be getting to know the instrument again after all these years.

‘It will take me first maybe two hours to go just through the organ, through each part,’ he says matter-of-factly. ‘It’s a little bit like if I was a conductor and I would have to shake hands of all the people in the orchestra just to know the character, the personality – and then when I know them a little bit better, then I'm able to make music with them.’

‘It’s exactly the same thing for an organ. So I need to listen to all stops alone, and then to listen how they will combine together until I get to the point where I say well this is the registration that I want. So that takes time.’

‘Each time you have to see and to find the way – what is the best sound for that musical moment, what is the best sound for the atmosphere of that moment, what is the best sound for the balance with the orchestra. It's really some kind of acrobatic situation each time.’

How exciting for Sydney to get to watch this high-wire act once more, high above the Concert Hall stage.

Book Your Tickets

Saint-Saëns' Organ Symphony

There’s no one better than virtuoso French organist Olivier Latry to take on the power of Saint-Saëns’ Organ Symphony, one of the most famous symphonies of all time. This work is pure feel-good romanticism, full of soaring emotional moments.

10–13 July | Sydney Opera House Concert Hall