Sir Stephen Hough: ‘Brahms stops us from being completely taken over by the machines.’

02 April, 2025

British pianist Sir Stephen Hough returns to Sydney in 2025 for two concerts, performing the first piano concertos by Brahms and Mendelssohn a couple of weeks apart. Here he discusses the similarities between the two men, the magic in their music, and why the flesh and blood of music like this is our best defence against the soulless void of AI.

By Hugh Robertson

You have all seen it, I’m sure, clogging your social media: torrents of soulless slop churned out by AI.

Whether infringing the copyright of authors on an industrial scale or directly copying the art style of beloved filmmakers, our tech autocrats glibly assert that ‘this is progress’ as they squeeze all of the joy and humanity out of art.

How do we combat this rising tide of computer-hallucinated garbage? If you ask Sir Stephen Hough, the answer could be Johannes Brahms.

‘I played Brahms in Seattle a year or so ago,’ recalls Hough, ‘and I had dinner with someone who was one of the heads of AI at Microsoft. And he said, “AI will never touch what Brahms did in that piano concerto because that is flesh and blood. That is sinew and muscle and a heartbeat and a brain. And we can of course get close in many areas of life, but Brahms stops us from being completely taken over by the machines.”

‘I’m an optimist in almost everything in life. And I wonder if we might actually begin to rediscover more how important those areas of life are which AI can’t help us with – whether it’s relationships, whether it’s art, and so on. And I think this could be a very exciting era in human life.

‘The youngest person playing Brahms, Chopin or Beethoven now is completely connected with what was going on 200 years ago. And we realize we’re the same human beings for all of our developments. And this connection.’

If anyone knows how to make a connection through music, it’s Hough. Over a professional career spanning 45-odd years and counting he has established himself as one of the world’s great pianists – ‘a keyboard colossus’, says The Guardian. He needs little introduction in Sydney: a frequent visitor since his debut with the Orchestra in 1992, his performances are always heavily-subscribed and highly-praised.

In 2025 we get to hear him twice in quick succession: first, performing Brahms’ Piano Concerto No.1 with conductor Elim Chan, then three weeks later tackling Felix Mendelssohn’s First led by Principal Guest Conductor Sir Donald Runnicles. It’s a great opportunity to hear him in two works that have a lot in common in many ways, but are worlds apart in others.

‘I like the contrast of the Mendelssohn and the Brahms,’ says Hough with his typical enthusiasm. ‘They're both of course Germans, from the 19th century. The Mendelssohn is perhaps the shortest piano concerto in the regular repertoire, and the Brahms First is perhaps the longest. So you get two sides of the same coin.

‘The Mendelssohn, structurally, is really sort of in one movement – or at least the three movements go into each other. The Brahms is very much three separate statements, but all of them monumental and deeply felt.’

Both concertos have been core works in Hough’s repertoire for many years, and he has recorded both to rave reviews. The Brahms in particular is very close to his heart.

‘It’s a piece that I never get tired of,’ he says. ‘There is always something more to find there, and it’s a work that makes a huge impact on me emotionally every time. I remember one performance when I really couldn't speak afterwards, I was tearing up. I just felt this darkness to light – which all of us look for in our lives in various ways – so overwhelming and such a deep human experience.’

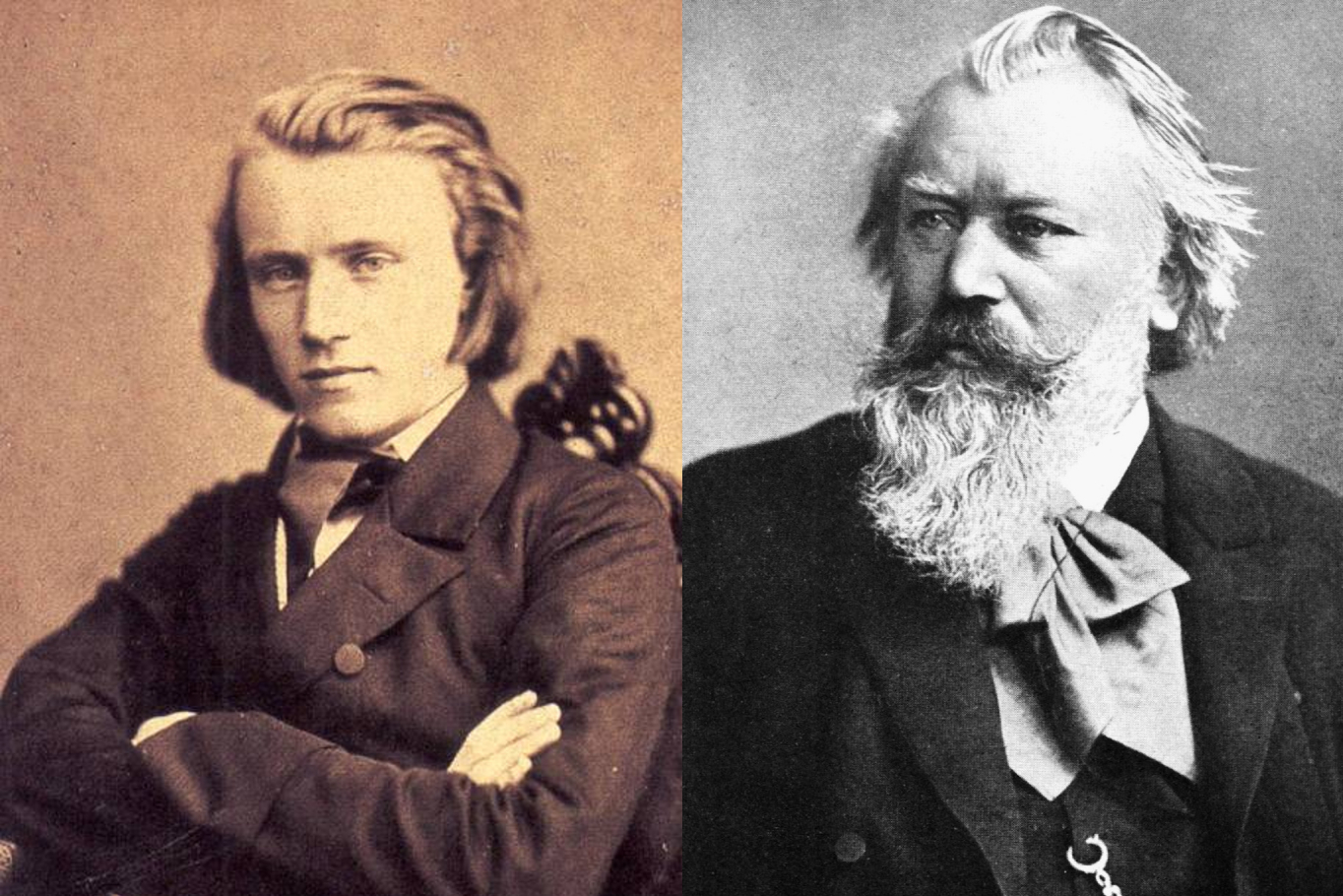

The popular image of Brahms is of him as a taciturn old man with a long grey beard, a respected elder statesman, one of the most significant figures in music in the second half of the 19th century. But of course he was young once – he wrote this first piano concerto when he was just 25 – as Hough is quick to point out.

‘He was an Adonis when he was in his twenties,’ says Hough. ‘And this piece is part of that time of his life. I think what's interesting is the emotions are much more open here than they are [later in his life].

This is a piece where the whole audience, collectively, can get what Brahms is about.

We sadly don’t get to experience a similar life-long engagement with Felix Mendelssohn, who died at the age of 38. But he had been a prodigious performer and composer from an early age, performing alongside his equally-talented sister Fanny before they had even turned ten and writing a significant number of works before he was 15.

Hough is no less enthusiastic about Mendelssohn’s concerto, written in 1830 when he was just 21 and displaying all of his prodigious talents.

‘I think Mendelssohn is absolutely wonderful,’ he says. ‘This is a fairly early piece… [but] there’s a lot of depth in Mendelssohn. It’s an earlier period. He's coming out of the Classical period in that wonderful era when you have these other composers who were expanding the piano and working with diatonic harmony, but making it vehement and passionate – and in fact fiery.

‘When I recorded all the Mendelssohn music I counted the number of times he'd written con fuoco, “with fire” in the score, and I think it was something like 14, and there's a good three or four in this concerto.

‘And you certainly hear that very much in the first movement of this piece. It’s a piece that begins with a massive crescendo, from the softest the orchestra can play to the loudest the orchestra can play in about five seconds. He really gives you a kick in the backside as you begin this piece – it’s a firecracker going off.

‘Then we have the second movement or the second section, which is one of his most beautiful songs about words; Mendelssohn wrote gorgeous melodies, they poured out of him. And then the last movement, yes, it begins with some of the fuoco of the first movement, but then we suddenly find ourselves in this marvellous world of froth and champagne and lightness. And, you know, let's not forget that that's human life too. Let's hope it is in all of our lives. And maybe a sense of humour is also something that AI can't do. And this last movement certainly has that. It has a smile in every bar and it's a very joyful piece to play.

The audience always has this wonderful reaction at the end because it's an irresistible popping of a cork.

One of the things that connects Mendelssohn and Brahms is that they were both pianists, as well as composers – something that Hough has in common with them, too. He has just released a recording of his own piano concerto, titled The World of Yesterday, adding his name to the long list of composer-pianists.

‘It began with Mozart, who was the great virtuoso of his time, and it became a vehicle for virtuoso pianists. Composers always wrote their own piano concertos until the second half of the 20th century – this goes right up to Shostakovich and Benjamin Britten. It was the calling card for composers to show people who they were.’

‘I think what's interesting is you actually do get a glimpse of how they played from how they wrote. With Brahms there’s a lot of chords, it’s very rich and thick – he obviously loved the piano full of resonance. And then with Mendelssohn, he must have had the fastest fingers in town because he loved to write these very gossamer-like, leggiero, finger figuration all over the keyboard. So you do get that little sense there.’

Hough’s concerto received its world premiere in January 2024, performed by the Utah Symphony under Sir Donald Runnicles, and Hough is excited to be reuniting with old friends for his performances in Sydney.

‘I just love working with him – he’s such a great musician,’ says Hough with a smile. ‘He has an individual voice, and it's kind of rare. Of course there are wonderful conductors around, but some of them just make the orchestra sound like nobody else. And Donald is one of those. So I’m very excited to be working with him.

‘And then the Brahms with [conductor] Elim [Chan], who’s a friend and absolutely fantastic, I'm excited very much to work with her. We last worked together literally the week before the pandemic began, and I’m so excited to be doing the Brahms with her.’

Returning to Sydney is also an exciting prospect for Hough, and it’s easy to see why he has accepted so many invitations over the years – not least because of his own Australian heritage: his father was born in Australia, and Hough became a dual British/Australian citizen in 2005.

‘What a joy it always is,’ he says with the biggest smile of our interview. ‘I’m often asked what are my favourite places to play, and I always have to say Sydney, for all kinds of reasons. I absolutely love coming back to play and to visit. And of course, the last time I was there, it was in the refurbished Sydney Opera House Concert Hall. So now I can say that I also love the acoustics!

‘How marvellous it is that they've made a success of that [renewal] without doing anything to the building itself. And I think it's a great, great joy. You really felt like you could hear other players and make a connection musically with them. Because it’s one thing hearing a clarinet play something, but it’s another thing hearing it in a way that it's actually enveloping you so that you can dance with it, you can put your arms around that sound and actually make movements with it and shape it. And that's something that you only get in the best concert halls. And I feel now that that's possible in Sydney. So that's very exciting, I think, for one of the great cities of the world.

‘And I can't wait to be back there in May.’